Dr Ollie Folayan, Co-Founder and Chair of AFBE-UK

The growing sense of optimism about diversity in the energy sector was in full display last week, at a talk we had been invited to give about the Ethics of Ethnic Diversity. I could tell from the number of attendees and the views expressed at the session, that the desire for change is real. I was also buoyed by the fact that this audience had representatives at various levels within the company – including management.

It is however important to understand that efforts like these merely reflect a desire for change, not the change itself. Our industry is still far from being a meritocracy and a coherent diversity and inclusion strategy that is hard-wired into their business plan, is not yet on most companies’ radar. This is evidenced by recent reports that the Scottish government has no targets to increase ethnic minorities in offshore wind and the observation made last year by the former chair of the equalities and human rights commission (EHRC), Trevor Philips that, “people of colour seem to be superglued to the floor”.

It is important that the current enthusiasm evolves into real change. By that I mean greater recruitment of minorities into the industry and support of their career progression within.

The first step to addressing an issue is to acknowledge its existence. The ‘nothing to see here’ stance of many leaders towards racial parity is still a key barrier to dealing with a problem. It is therefore important to face up to the issues by addressing some of the perceptions that surround ethnic diversity versus the reality.

I have explained three examples below.

- Perception#1 Ethnicity is Irrelevant in 2020

I still meet well-meaning people who justify the status quo by suggesting that anyone who suggests that race is still a factor must merely be playing the race card. But there are a few things wrong with this view. Firstly, it presumes to understand the impact of race better than the people most affected. Secondly, it often overlooks the fact that we all have unconscious biases which can sometimes influence our opinion on how an outcome has been achieved at work. Thirdly, this view fails to consider the systemic root causes of black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) underrepresentation in engineering.

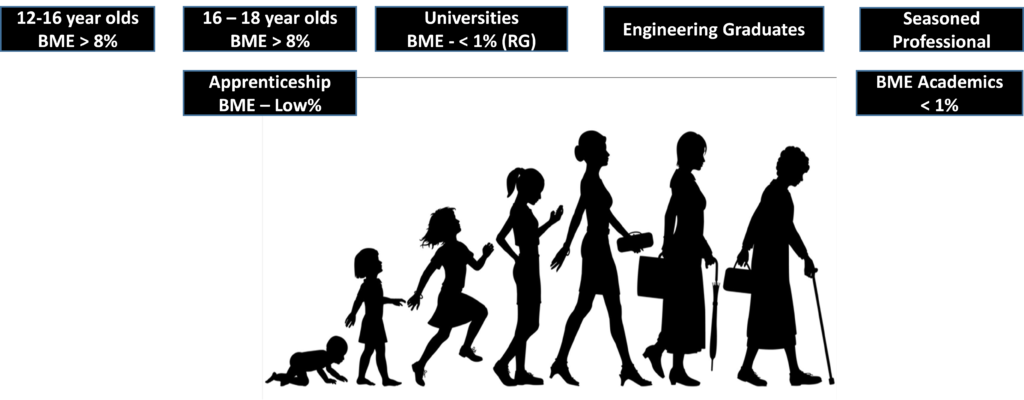

Racial disparity begins at the very early stages of education, where many people from BAME communities have neither the quality of education, nor the family support, to maximise their potential in STEM subjects. This results in many BAME people missing out on places in the better-funded universities and consequently over time, lower employment rates with the more reputable companies. When these young people secure employment – often after a longer period of searching than their counterparts – they enter an industry in which they have few role models in positions of influence or the support networks to help them make good career decisions. This is often reflected in the pay gap.

Flowchart showing career progression of a typical UK BAME Engineer[1]

According to the 2019 update to the Engineering UK report, six months after graduating, BAME engineering graduates in full-time work earned on average £507 less than their white counterparts. The pay gap was particularly wide for black engineering graduates (£24,924) compared with white engineering graduates (£26,220) – a difference of £1296.

- Perception#2 They have all come from Overseas

There is a perception that most BAME engineers within the UK are from overseas, but the reality is that more are UK-domiciled than from overseas. The 2019 update to the Engineering UK report reveals that students from BAME backgrounds accounted for 31.8% of UK-domiciled first degree entrants, compared with 25.6% across all subject areas. For taught postgraduate entrants 32.7% (compared with 22.5%) and 21.7% of postgraduate research entrants (compared with 16.5%) were from BAME backgrounds. This is compared to 7.8% of the engineering workforce.

- Perception#3 “Minorities don’t apply for jobs in our company”

This is often a justification given by companies with low minority ethnic representation. In my experience as an engineer, having worked in some remote locations in the UK, I have often been surprised by the level of diversity in such companies. It seems that the barriers to minorities making applications could be influenced more by job marketing and other recruitment practices than minorities refusing to apply.

A serious drive to achieve racial parity must therefore involve:

- A focus on long term growth – Although short term targets/quotas provide a means of tracking and reporting progress, they are only useful if they are part of a broader agenda that looks at providing the resources to enable career progression i.e. 10-year programmes as opposed to 2-3 year quotas.

- Acquiring Data: One of the key problems is the dearth of data in this area. Such research will help the business case for more investment in this area.

- Benchmarking Progress: The survey commissioned by the OGUK Diversity and Inclusion Task Group will help the oil, gas and energy industry to establish a baseline. Progress tracking can then follow on from that.

- Greater investment: Targeted funding of STEM education in inner city schools and relatively deprived areas where BAME communities often are, will help to create an enabling environment.

- Enabling Transition: Addressing the relatively low uptake of BAME students in Russell Group universities. Much is made of the low numbers of BAME students in Oxford and Cambridge, but the problem affects other reputable universities as well.

- Ensuring Cohesion: Improving integration between industry and schools and government-led incentives for companies that invest in STEM in their communities. In an article in the Guardian last year, Careers expert, Ava Miller observed that poor careers advice at university hits minority students hardest and identifies AFBE-UK’s Transition programme as a scheme which has helped struggling attendees to find work after graduation.

- Identifying Role Models: Greater visibility of engineering role models from BAME communities in culture and society at large.

- Involving the voluntary sector: Increased support for local grassroots initiatives rather than an emphasis on large events. The role of these often underfunded local groups is underappreciated, but they understand the needs of their communities more than most – and are often better placed to raise the aspirations of young BAME people.

- Incentivising: Companies not only being held accountable but also being rewarded and recognised for their efforts at achieving diversity and inclusion.

These steps must form an essential part of any diversity strategy if the current zeal for diversity is to evolve into substantive change.

Dr Ollie Folayan is an experienced process engineer and combustion specialist with a background in the oil and energy industry. He is Principal Process Engineer at Cleofol Enterprises Ltd and Chair of AFBE-UK Scotland.

AFBE-UK is a not-for-profit organisation providing support and promoting higher achievements in Education and Engineering – particularly among students and professionals from ethnic minority backgrounds.

Read more about AFBE-UK’s work here

[1] Extract from AFBE-UK’s paper published in:

R. Bhamidimarri and A. Liu (eds.) Engineering and Enterprise, ©Springer International Switzerland 2019, ISBN-10: 331927824X, ISBN-13: 978-3319278247, pp 75-82